|

| Scott Greene, "FUBAR", 2007 |

|

| Antonello da Messina, "Crucifixion", 1475, National Gallery, London |

There is the moral of all human tales;

‘Tis but the same rehearsal of the past.

First freedom and then Glory--when that fails,

Wealth, vice, corruption--barbarism at last.

And History, with all her volumes vast,

Hath but one page…

Allegory painters are the prophets of each generation. They use familiar images to convey weighty social or political concepts relevant to their specific time in history. They reflect the world back to us as it is, but with their own fantastical understanding of where it is headed. Scott Greene is one such painter. He uses familiar imagery, like the landscape, detritus of human life, and animals, to remind us of how our presence on this planet impacts nature. He paints all these subjects with such exquisite beauty, that we cannot help spending great amounts of time contemplating his messages. Greene says of his work:

I employ the language and finish of classical painting, deriving inspiration from both art history and the contemporary social environment, in order to examine and satirize the relationships between politics and nature, and between beauty and the unpleasant.

Greene’s painting, "FUBAR" (F’d Up Beyond All Repair, from military slang), uses the allegory of the crucifixion to portray how contemporary mankind has “crucified” the environment. He was inspired by a crucifixion painting from over 500 years before, by Antonello da Messina. While Messina's painting features an idealized landscape in the background, Greene portrays a bombed-out Iraqi landscape in the background of "FUBAR". His cross is draped with extension cords and discarded electrical gadgets, to assert our national over-extension in the Middle East at that time.

Scott Greene, "SNAFU", 2015, Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Scott Greene, "SNAFU", 2015, Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, “Portrait of Countess D'Haussonville.” 1845, Frick Collection, New York

In "SNAFU" (military slang for Situation Normal, All F’d Up), an overflowing suitcase becomes an allegorical symbol for our generation’s decadent opulence. I see the suitcase as an overstuffed container of human life, spilling out the excess we have accumulated. I am reminded of a formal painting by Ingres, from the early days of Industrial Revolution. Ingres paints the young countess wearing a gorgeous blue silk dress; satin ribbons in her hair. The interior in which she stands is adorned with rich furnishings and flowers. She seems young, hopeful, and confident about her future. In Ingres’ painting, the earth had not yet been severely polluted by industry, so there was a lot of prosperity and possibility on the horizon. But by 2015, when Greene painted "SNAFU", humankind had definitely “F’d Up” the environment. Marshmallows are strewn on the dirty ground; the only green in site is discarded fabric or carpet, standing in for the absent grass. A pink chemical bonfire burns from thrown out pipes.

I employ the language and finish of classical painting, deriving inspiration from both art history and the contemporary social environment, in order to examine and satirize the relationships between politics and nature, and between beauty and the unpleasant.

|

Greene writes of the painting:

"SNAFU" is a parable of sorts about making the best of a bad situation. It depicts a make-shift bivouac with a blazing campfire for warmth. Wood appears to be scarce, so a pile of PVC pipes are used instead. Bits of food and debris are strewn about, with all the fix’ns for some very smoky s’mores. I was inspired by a homeless person (possibly a whole family) who established an encampment in our irrigation ditch last summer. It was a very organized campsite, with tarps, suitcases, backpacks and cooking utensils. Because of the nature of the objects (specifically food and fire) and their close proximity, I also see this belonging to the genre of vanitas painting - meaning art that reminds people of mortality and that material things are ephemeral.

Scott Greene, “Exhaust” 1992-94, 132 x 192” Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art, Roswell, New Mexico

Scott Greene, “Exhaust” 1992-94, 132 x 192” Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art, Roswell, New Mexico

Scott Greene’s “Exhaust” was inspired by Theodore Gericault’s painting “The Raft of the Medusa,” with its message of desperation and hope. When Greene first saw the monumental painting at the Louvre, he was struck by its impact and detail. He writes, “My intent was to create a modern version of his History Painting, a contemporary equivalent with environmental issues as a core theme.”

Theodore Gericault, “The Raft of the Medusa” 1819, 192 x 276”, Musee du Louvre, Paris

Gericault’s painting portrays the darkest tendencies of humanity. The Medusa was a ship that crashed while attempting to colonize Senegal, necessitating the crew’s hasty fabrication of a raft. Many escaped via suicide, others threw weak and injured overboard to save themselves; some even turned to cannibalism. Likewise, Greene’s “Exhaust” addresses contemporary man’s attempt to overtake nature, via dependency on fossil fuel (see the upturned, empty gas can) and depletion of natural resources. Just as the crew members of the Medusa were left desperately stranded due to national greed, so is contemporary man left forlorn, in the deluge of environmental problems he has wrought.

Both artists reserve one small grain of hope. In Gericault’s painting, the men try to flag down a boat for help. It is so far away that it is barely visible in the painting, so chances are slim it will reach them in time. Greene places a small surfer riding a wave; a small hope for survival.

Scott Greene, "Big Dish Candy Mountains", Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

The painters of the Hudson Valley School were inspired by Romantic painters such as J.M.W. Turner, as they painted the sublime beauty of unspoiled nature in the United States. They would paint views from afar; dreamlike visions of the landscape. Scott Greene employs some of the same aspects of romanticized, mystical landscape as Hudson Valley painter Sanford Gifford, in his "Big Dish Candy Mountains". In Greene’s painting, however, mountains of satellite dishes become the view--evidence of human imposition on the environment. The painting is part of a series of works he made in which the satellite dish symbolizes our inability to communicate, in spite of the proliferation of communication technology. Greene writes that "Big Dish Candy Mountains" was inspired by the "great hobo song 'Big Rock Candy Mountains,' about a make-believe place where lemonade rivers flow, and trees sprout cigarettes. A place where all your dreams come true, and you are never wanting for anything."

Sanford Gifford, "A Gorge in the Mountains", 1862

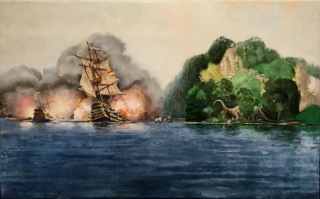

Hudson Valley School founder, Thomas Cole, created a series of five allegorical landscapes titled “The Course of Empire,” from 1832-1836. Cole meant his paintings to symbolize man’s imprint on the natural world. Greene contemporizes the concept, creating a series of paintings that reach from the time of the dinosaurs through Manifest Destiny, nuclear testing, to the melting of the ice caps. Unlike Cole, who pictured a time-lapsed version of the same scene, Greene sets his paintings at different locations across our country.

Scott Greene, "Course of Empire" series ("Peace Offering", "Manifest", "Testing One Two", "Eminent Domain", "Shelf Life"), 2015, Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

| Theodore Gericault, “The Raft of the Medusa” 1819, 192 x 276”, Musee du Louvre, Paris |

| Scott Greene, "Big Dish Candy Mountains", Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico |

The painters of the Hudson Valley School were inspired by Romantic painters such as J.M.W. Turner, as they painted the sublime beauty of unspoiled nature in the United States. They would paint views from afar; dreamlike visions of the landscape. Scott Greene employs some of the same aspects of romanticized, mystical landscape as Hudson Valley painter Sanford Gifford, in his "Big Dish Candy Mountains". In Greene’s painting, however, mountains of satellite dishes become the view--evidence of human imposition on the environment. The painting is part of a series of works he made in which the satellite dish symbolizes our inability to communicate, in spite of the proliferation of communication technology. Greene writes that "Big Dish Candy Mountains" was inspired by the "great hobo song 'Big Rock Candy Mountains,' about a make-believe place where lemonade rivers flow, and trees sprout cigarettes. A place where all your dreams come true, and you are never wanting for anything."

| Sanford Gifford, "A Gorge in the Mountains", 1862 |

Hudson Valley School founder, Thomas Cole, created a series of five allegorical landscapes titled “The Course of Empire,” from 1832-1836. Cole meant his paintings to symbolize man’s imprint on the natural world. Greene contemporizes the concept, creating a series of paintings that reach from the time of the dinosaurs through Manifest Destiny, nuclear testing, to the melting of the ice caps. Unlike Cole, who pictured a time-lapsed version of the same scene, Greene sets his paintings at different locations across our country.

Scott Greene, "Course of Empire" series ("Peace Offering", "Manifest", "Testing One Two", "Eminent Domain", "Shelf Life"), 2015, Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Scott Greene, "Mistletoe", 2015, Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Scott Greene, "Mistletoe", 2015, Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

May we all learn from these images. Visual language doesn't preach to us; it allows us complete freedom to contemplate these issues in our own minds, and come up with our own answers to difficult problems.

To hear Scott Greene speak about the environmental symbolism in his paintings, please join us on Friday, March 11, at 6 pm at Turner Carroll Gallery, 725 Canyon Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

You can also view Scott's paintings at the New Mexico Museum of Art, until April 24; Turner Carroll Gallery, and Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art in Roswell, New Mexico.

End of Part 4

Tonya Turner Carroll

Turner Carroll Gallery and Art Advisors

Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

turnercarroll.com

To hear Scott Greene speak about the environmental symbolism in his paintings, please join us on Friday, March 11, at 6 pm at Turner Carroll Gallery, 725 Canyon Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

You can also view Scott's paintings at the New Mexico Museum of Art, until April 24; Turner Carroll Gallery, and Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art in Roswell, New Mexico.

End of Part 4

Tonya Turner Carroll

Turner Carroll Gallery and Art Advisors

Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

turnercarroll.com